Way back in the hazy days of Army history (1905), there existed a mythical bird: the Oozlefinch. First sighted by inebriated denizens of the Coast Artillery Corps Officer’s Club at Fort Monroe, Virginia, the Oozlefinch was quickly adopted by that corps as their mascot. Allegedly featherless but with large eyes with which to see the enemy, the Oozlefinch was not the most graceful bird. While the Oozlefinch could fly, it could only do so backwards. Like the corps of which it was the mascot, it was misunderstood, much maligned, and never given full recognition. The Coast Artillery Corps faded into obscurity at the end of World War II, and along with it, their motto: “Quid ad sceleratorum curamus,” translated loosely as, “What in hell do we care?”

The equally odd Air Defense Artillery branch has replaced the Coast Artillery Corps, but I believe that the motto should be taken over by all staff officers, everywhere. For staff officers, like the Oozlefinch, are a misunderstood and downtrodden bunch.

“What do staff officers even do?” clamor the masses.

Well that’s a damn good question.

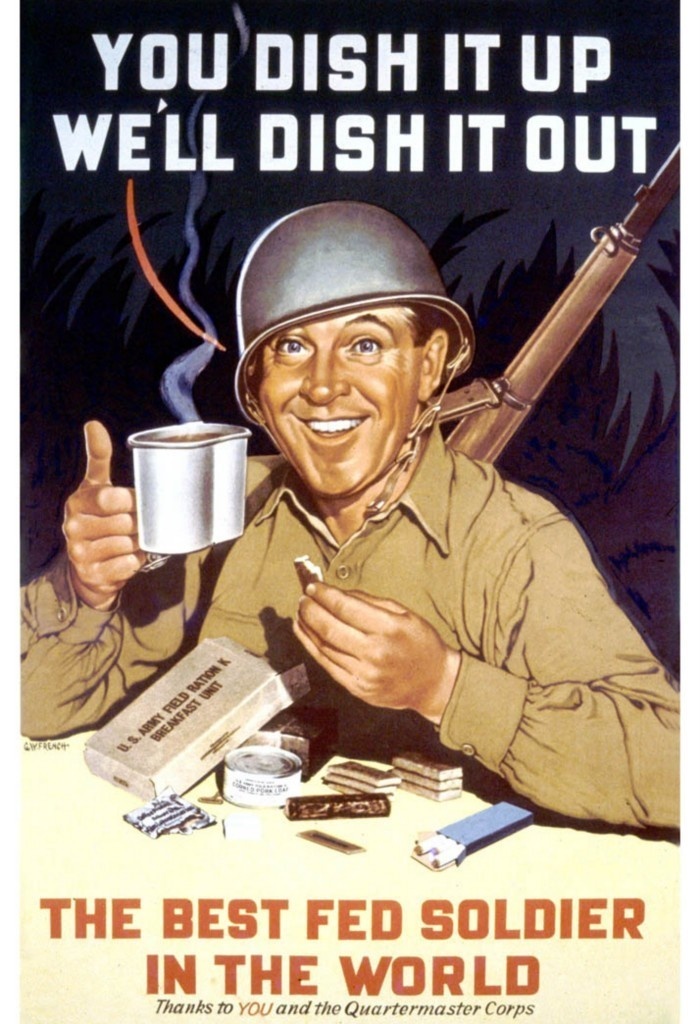

We drink a lot of coffee. That is step one. Eyes bleary with lack of sleep from either writing an order all night or from a marathon game of Skyrim, staff officers are attached to their coffee cups by a death grip. On a recent morning, coffee clenched firmly in hand, I stumbled into the conference room for staff call. No, this is not an actual call, like one would call pigs or dogs or ducks, although often that would be helpful. Staff call is a meeting of the minds.

“The best minds?” comes the query.

Well, something like that. The commander gathers together all the heads of the various staff sections and then they proceed to brief him or her on the status of his or her organization.

“From memory?” you ask.

No, of course not, from PowerPoint slides that have been put together by their subordinates. The higher in rank staff officers go, the more of their subordinates they have put together their briefings. Thus, when a general officer of the three-star variety is speaking, know that some captains have done a lot of work to put those words together.

“Couldn’t the captains just brief for the general?” ask the uninitiated.

Of course they could, but no one would listen. Company grade officers are better seen but not heard, and are even better when they are neither seen nor heard. It is the gravitas and persona of the general that makes the message important.

“Your cynicism betrays you,” say you.

Damn right it does. Where squids shoot oil as a defense mechanism, so staff officers wield the double-lightsaber of cynicism and sarcasm, in order to make their way through the world. Back to staff call.

Sitting around a large table, the staff is seated by seniority. Colonels hold the inner seats, circling the commander or chief of staff like so many planets or moons. Lieutenant colonels and majors cluster just back of them, papers rustling, ready to jump in if called upon. Sergeants major lurk in belts, like asteroids, uncertain of their duty but ready to ram a spaceship or officer if needed. The outer circle is made up of sardonic captains, who see this all as a giant game in which to pit the higher-ranking officers against each other. Captains somehow always look self-composed and cool. And then, far out into the ether, is me, a lieutenant, as confused as to my purpose there as Pluto is to whether it is a planet. Hours seem to pass, and then, the ether clears and all of a sudden it’s my turn to brief.

I have a theory about staff calls, staff meetings, and staff huddles: they are all designed to add more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. This is the only explanation for how long they drag on. So I have a rule: if I am briefing one slide, I will spend less than one minute on it. I will brief a maximum of four points on that slide, preferably ones that need more explanation, because I know that colonels can read and make inferences. At the end of my sub-minute brief, I ask if there are any questions, in case there was that one person out there that cannot read.

It’s PowerPoint, people, the words are all on the screen. Build a slide correctly, and you hardly have to talk.

Following staff call, or staff meeting, or battle update brief, or any of the other meetings, a staff officer’s world plunges straight into more writing, mini-meetings with other staff officers, much more coffee, phone calls, emails, and an overwhelming sense of self-loathing. And since lieutenants and captains stay late to do so much of the grunt work, they are often literally plunged into darkness as their superiors shut out the lights and leave the building. And the kicker? Even if you do a good job, it may never make it through the bureaucratic mess that is the Army.

“Well this is just the saddest thing, ever,” you say, leaning your head on our shoulder.

I know, it is.

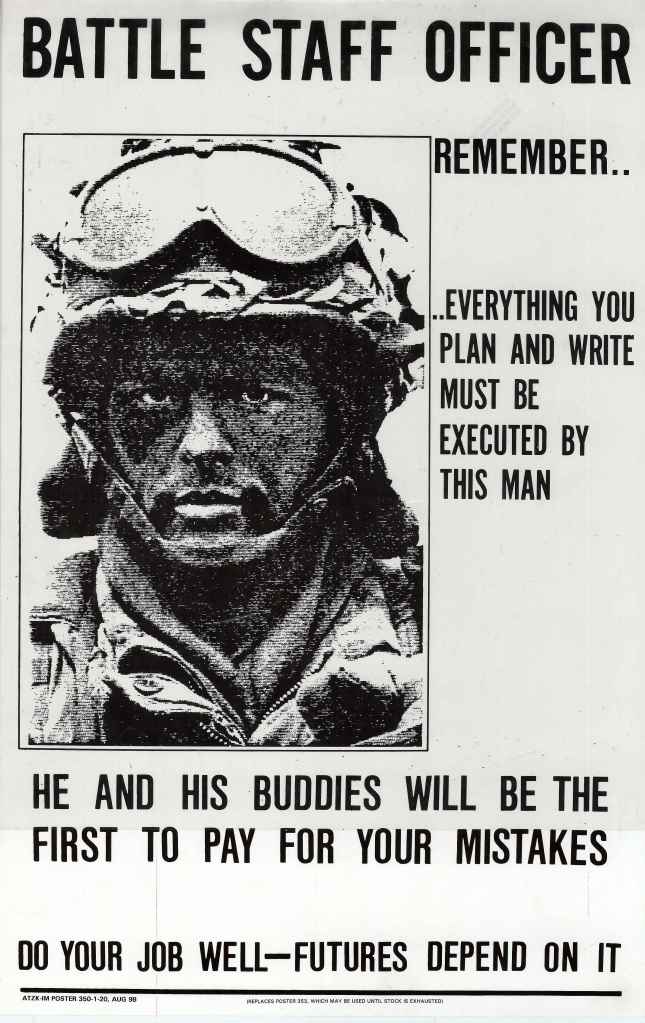

Well, it’s not always. Where it pays off is those times you can help the guys and gals in the field, the ones in the line units, the ones carrying the guns, hauling the gear, building the roads, flying the sorties, in all types of elements, day and night, weekend or weekday. If you can make their lives easier, get them better assets, give them better training, get them a hot meal when it’s cold and maybe a roof when it’s raining, anticipate their needs, and help them accomplish their mission, then it’s worthwhile. If we can honestly know that we did our damnedest to support the Soldiers down to the very lowliest private, and did everything we could to support that company, battalion, or brigade commander accomplish their mission, then it’s a rewarding job.

“But that doesn’t sound like you get much recognition?” you ask.

“What in the hell do we care?”

We’re staff officers.

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by hitting the blue star “Like” button below and sharing it on social media.

Great post. I actually was wondering what a staff officer does.

LikeLike

The poor assumption here is that much of what a Staff Officer does truly affects those on the line. But thanks to poorly organized and/or misguided CDRs and XOs, little of what these Staff Officers do trickle down to the line. Instead it just “makes sausage” and perpetuates more work from within. I believe self-licking lollipop is the vernacular…

There is nothing so important on a staff that its members should be staying late or surviving off of caffeine. But we created a culture where success can only be measured in man hours instead of achieving a mission, and so we truly believe our work matters. It doesn’t. If the military hasn’t fallen apart every year during “American Rammadan” ( that time between Thanksgiving and New Years where no work gets done) then it proves that the work of a staff really isn’t as important as it’s made to sound.

LikeLike

I find myself nodding to what you say, except that I’ve seen some damn fine staff officers. And some very functional staffs. And of course, the complete opposite. The system works, somehow.

LikeLike