I’ve been mulling over this idea of going back and revisiting old favorites, both in literature and film. If you’re like me, you read a lot of books growing up and probably had your favorites that you revisited time and again. Same with movies, TV shows, and documentaries. As we’ve gotten older – and our available time has diminished – we find ourselves less able to go back to read or watch our old favorites. This is a shame, because as we grow older and garner more life experience new levels of meaning rise to the surface. A prime example is J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings saga. As a teenager I read and re-read these books until the covers fell off, fascinated with the world and adventure it created. It was not until I returned from a deployment to Afghanistan that I found a deeper meaning in Tolkien’s writing, one that had a personal connection to me as a veteran: the difficult transition from soldier to civilian.

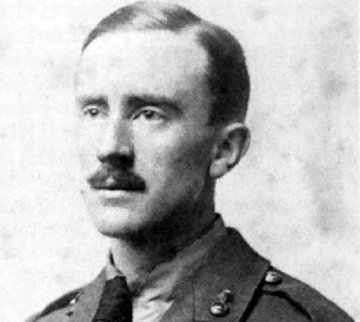

Tolkien knew this transition very well, as a citizen-soldier veteran himself. After graduating from Oxford in 1915, Tolkien joined the ranks of Britain’s volunteer army in World War I. As a civilian, he chafed at the rigid discipline and class structure of the British army that kept him from developing a personal connection with the men under his command. After the war he wrote, “The most improper job of any man… is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity.” He arrived on the front as a signal officer one week after the horrific Battle of the Somme, where 20,000 British soldiers were killed in action. On the first day alone. His time on the front impacted him deeply, as did the loss of so many of his friends. Indeed, in his forward to The Lord of the Rings, he writes, “One has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel fully its oppression; but as the years go by it seems now often forgotten that to be caught in youth by 1914 was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years. By 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.” Tolkien came off the front lines in late 1916 because of illness, but the war stayed with him for the rest of his life. For more on how the Great War impacted his writing, read this excellent post.

One of my favorite part of the series was the portion in The Return of the King, entitled “The Scouring of the Shire.” It was regrettably left out of the movie adaptation, one of many flaws for which I hold Peter Jackson accountable – but that’s another rant altogether. “The Scouring of the Shire” tells the story of the hobbits’ homecoming to a home that is drastically changed. It is the story of combat veterans returning to a world that they are completely unfamiliar with. As the hobbits ride in, still wearing their raiment of war – helmets, armor, swords – they are greeted by friends and family who stare at them in amazement, unsure how to deal with the transition of their formerly fun-loving friends to hardened warriors. Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin are taken aback, not having seen themselves as having changed, being fully used to travelling armed, in groups. Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan can immediately see the comparison to the first time they got into a civilian car when they returned home. It seemed odd to not be travelling in an armed convoy, always hyper-aware of enemy threats, or not having your weapon at arm’s reach.

The protagonists struggle with how to deal with this transition in different ways. Sam, Merry, and Pippin, being younger and more resilient, channel their energy into transforming their community and using their new skills to rid it of the evil influences it has fallen under. They start families and become leaders in their community. This is true of the vast majority of our veterans. But for Frodo, the pain and trauma of the “War of the Ring” is not easily thrown off.

Frodo is shaken by what he has seen and experienced, and displays very obvious symptoms of post-traumatic stress. On every anniversary of his wounding he is haunted by grief and pain. For many of our combat veterans, anniversaries of battles or losses of friends can be traumatic times. Frodo is unable to emerge from a larger depression on the war and all the loss it has caused. His comrade in arms, Sam, tries to get him out of his depression. Frodo responds, “I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them so that others may keep them.” This is the true cost of war, the cost that so many have paid in fighting for our country.

In the end, Frodo cannot live with his pain any longer and leaves Middle Earth to go with the elves over the sea where he can live in peace. This always struck me as somewhat sorrowful, but yet still happy, as he found joy somewhere else. In reality, it is far, far more tragic than that. For veterans, there is no similar escape. Many choose the final escape from their pain through suicide. In essence, this is what Frodo does as well. This work of fiction underlines the importance of helping veterans connect with the world again, to help them find joy and fulfillment that can outweigh the pain and depression they carry. We cannot let suicide be the answer.

For Tolkien, war was never very far from his mind. His good friend C.S. Lewis had been wounded in the Somme during the war, and the two shared the bonds of combat veterans. Tolkien’s son, Christopher, served in the Royal Air Force during World War II, surely causing his father great fears for his safety. Tolkien treated the peculiar mixture of boredom and fear that war brought by writing while he was in the trenches. Perhaps his great work after the war was part of his way of dealing with his own trauma and “survivor’s guilt” – most of his battalion was wiped out in the weeks after he came off the lines. If so, then it is a sign of how cathartic writing can be, and how valuable it is for veterans to be able to use it as a release. In writing, we can escape, we can create our own worlds, futures, and outcomes. It offers something that we can control, when often so much of life seems completely out of control. For those struggling with the transition from war to peace, or with their own inner demons, writing offers untold solace.

Enjoy what you just read? Please like or share on social media using the buttons below.

You can see a lot of Tolkien’s war experience in LOTR. The mechanisation and dehumanising of the enemy comes through in the Orcs. The hobbits are the country volunteers.

BTW the first day of the Somme was 20,000 killed and 40,000 wounded in one day. Probably the British Army’s worst day ever. The Battle of the Somme lasted from 1 July to 18 November 1916. We’re in the throes of the centenary commemorations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For tormented minds struggling with their demons, depressions, and horrific memories, writing does indeed offer solace. This need not involve literary ambitions. Simply scribbling whatever is inside your head into a rough notebook can be all that’s needed to externalise the problem. This not only frees the mind for a little time, to enable a degree of rest and recuperation, it also cuts the problem down to size so it becomes less overwhelming. When you see it all laid out in that little notebook, it becomes less insurmountable, something you can deal with, which you can prioritise and re-organise, and thereby build yourself a pathway out of hell, a step at a time. There are always ways around problems, and this is your way of finding them. And as the darkness dissipates, you will be amazed at the vistas which open up before you. Life is, and will again be, wonderful.

LikeLike

This is a very fine meditation on LOTR and war, and if you were closer, I would buy you a pint (English warm bitter, of course) and offer you some pipe tobacco. When I was a kid, like you, I read the books to tatters. One thing I never understood, and always found dissatisfying then, was why didn’t the hobbits come back to the Shire as heroes and live happily ever after as celebrated heroes? To my young mind, that ending just seemed to make more sense than the haunting tone that Tolkien ends on. Now like you I am a soldier and older (older than you by a bit, I think) and thanks to your essay, I can see it now. Doubtless Frodo was speaking for Tolkien,s own pyschic and moral injury when he spoke of his unhealed wound.

It’s interesting to think of how Tolkien spent his post-war years in relation to his experience as a veteran. While he was a well-known scholar (I used his text on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight) when I was a grad student, he was not all that prolific, preferring to spend his time in his garage writing to being in the classroom. I recall reading that Oxford wanted to fire him for dereliction of duty as a professor, but his friend C.S. Lewis (himself a veteran of the Great War), who was a far more successful public intellectual than Tolkien, managed to save his friend’s job. It’s interesting that Tolkien and Lewis both spent much of their later lives creating imagined worlds, perhaps as an act of healing and self-therapy? There is doubtless a PhD dissertation there somewhere.

This is a long-winded way of saying thank you for your thoughtful post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m always struck by how Tolkien described battles by focusing more on the preparations than the fighting. Soldiers arrive, pledge to do their duty, and quietly prepare themselves for certain death in support of a hopeless cause. The battles themselves are jumbled, unstructured messes. Preparing to die is a long, agonizing process; getting killed is quick and easy. Given his experience on the Somme, it seems like a fitting way to view war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As it happens, I have been reading Tolkien’s Letters. Several day ago I read the one World War I era letter included, It is dated August 12, 1916, during the Somme. He has heard that his close friend, Rob Gilson, had been killed on the first day of the battle and writes to another of his close friends, G.B. Smith, who himself was to be killed in a few months, that they would keep July 1st as a special day for all their lives.

I has never really understood why, in the context of Tolkien’s secondary creation, the anniversaries of Frodo’s wounding should be so bleak for him. I did not see the “mechanism” for that to work. Your statement that anniversaries are a traumatic time for veterans, suddenly made things click. Perhaps Frodo’s distress on the dates of his woundings, is a reflection of Tolkien’s holding the anniversaries of his friend’s death as “special days”.

As a non-veteran, I find the struggles of veterans of combat difficult to understand. I could think about combat and think that must be horrid, but I never really had an inkling of the emotional impact. Now just as you find parallels between the Hobbits’ lives and the combat veterans’ return from combat, I can now, because of your post, use Tolkien to get a shadow of a glimpse into the minds of my friends who have been to war.

Thank You.

LikeLike

As one who never served I cannot comment first hand on these issues. I just want to say I appreciate your insights into them. Some of this is mentioned in “The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien”. It gave me new insights of my favorite author. I share your ire at Jackson’s treatment of the Books. His massive divergence from them. As for the “Hobbit” trilogy, even worse. I found “The Desolation of Smaug” un-watchable.

LikeLiked by 1 person