There’s one of those old pithy military sayings that is so old that it has been attributed to everyone and no one: “Friendly fire – isn’t.” I’d like to paraphrase that regarding military terrain: “Impenetrable terrain – isn’t.”

Terrain is one of those features of military history and analysis that I feel never gets its full due (although I do highly recommend this work). From tactical combat to sustainment, so much depends on terrain: troop movement speed, line of sight for weapons, ability to move some vehicles into certain terrain, availability of bridging assets for rivers, placement of obstacles, and invasion routes, to name a few.

In the Army, we conduct terrain analysis in our Military Decision Making Process as part of the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield. Intelligence and engineer officers work together to create overlays that provide maneuver commanders a snapshot of how the terrain will impact their operations. To translate complex topography into terms that the crayon-eating infantry can understand – kidding, love you all – we classify terrain as unrestricted, restricted, or severely restricted. The latter is classified as terrain that slows mobility to the point as to be practically negligible. Often times, commanders look at the severely restricted terrain and write it off as either useless for them to try to maneuver in or think that the enemy won’t use it. Which is a mistake, as history tells us. Let’s take a look at some times that supposedly severely restricted terrain was overcome by the imagination, ingenuity, and perseverance of military leaders and their troops.

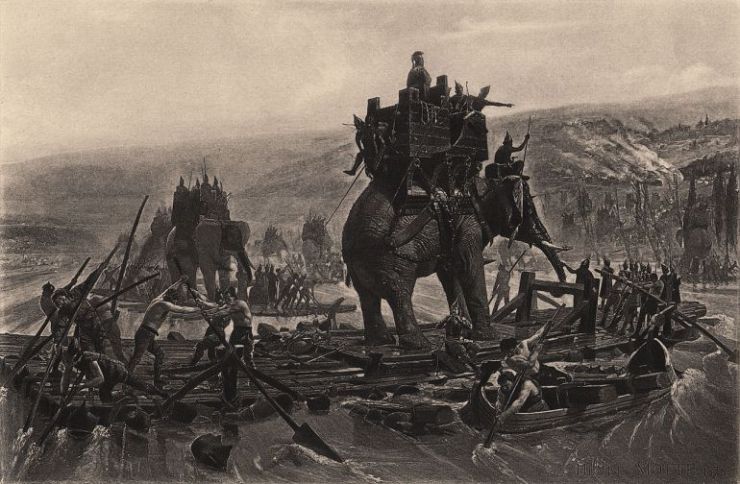

1. Hannibal Gets His Armor Over the Alps

The first of course is the famous Carthaginian general, Hannibal Barca. In 218 B.C., Hannibal decided to take his war with Rome from his home in Africa to the very steps of Rome itself. Rather than crossing the Mediterranean, he took 100,000 troops and forty war elephants on an epic march up through Spain, over the Pyrenees, and into southern France.

Here he was confronted by the Alps, apparently impenetrable, especially with his war elephants, the heavy tank of the era. Unfortunately for Rome, Hannibal didn’t much care for the lives of his men, so up they went into the Alps. After fifteen days, Hannibal’s Army came out the other side, reduced in strength by about 75%, but with nearly all their elephants still combat effective (side note: how do you PMCS an elephant?). He then ran rough-shod over a couple Roman armies and invaded further into Italy. His downfall came in that he had very little in the way of reinforcements and eventually had to abandon his campaign. Still, he’d gotten his troops on the soil of the Italian peninsula, scaring the bejupiter out of the Romans. But he also failed to anticipate the second and third order effects of his actions, in that the Romans were so mad that he’d humiliated them that they did a full court press on Carthage, invaded it, and defeated Hannibal at the Battle of Zama. But hey, elephants.

2. Knox Tames the Berkshires

The next example comes from our very own American Revolution. In 1775, the American forces were hanging tough against British-occupied Boston. They had one crucial shortage: artillery. Without heavy guns, George Washington could not expect to mount any type of successful offensive against the British forces who were well entrenched around the city and protected by the powerful guns of the Royal Navy. Thanks to the actions of Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold in May of that year, the patriot forces did have a supply of cannons and gunpowder at Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. However, Fort Ticonderoga and Boston were divided by 300 miles of mountains, forests, and rivers. Back before the Mass Pike, there were few reliable roads through the Berkshire Mountains; certainly none that could accommodate the heavy ox trains that would be needed to haul the artillery. Ever the optimist, Washington dispatched his chief of artillery, Henry Knox, to see if the impossible could be made possible. Knox arrived at Ticonderoga on December 5, just in time for the New England winter to set in. Unfazed, Knox started his journey with 60 tons of artillery and equipment.

His men blazed trails through mountain passes, crossed ice-covered rivers, and hauled the heavy guns up and over steep terrain. After six weeks, Knox arrived outside Boston, not having lost a single gun. In March, Washington then moved the cannon up onto Dorchester Heights, overlooking the city. The British awoke one morning to find their entire position ranged by powerful artillery. British General Howe is said to have exclaimed, “My God, these fellows have done more work in one night than I could make my army do in three months.” Unable to reach the rebel batteries with their own guns, the British abandoned Boston, proving the maxim that you should never underestimate crazy people who are willing to haul cannons over impassable mountains. We’ll see this maxim again.

3. Swamp? What Swamp? Grant Takes Vicksburg

In early 1863, Ulysses S. Grant was eyeing the key Confederate city of Vicksburg, which controlled the free passage of the Mississippi River. If U.S. forces could take Vicksburg, they could cut the Confederacy in two and curtail enemy supply movements. The problem: Vicksburg was a natural fortress, situated on high ground and surrounded by all sorts of impassable terrain features, such as rivers, swamps, and bayous. To even get at the city without walking right into the Rebel guns, Grant had to find a way to get close enough. He tried all sorts of crazy schemes – such as digging canals through the swamps to try to float the Navy downriver without being under the guns of Vicksburg. But these did not pan out. So Grant devised another way of getting his troops below the “Gibraltar of the West.” His troops would build a 70 mile road through a supposedly impenetrable swamp on the left side of the Mississippi, allowing Grant to move his troops down below the city. He could then cross the river and move on Vicksburg from the south. His men built bridges and corduroy roads – roads made of felled trees – through the swamps, until there was finally a route that could accommodate not only infantry, but their artillery and supply wagons. The Navy – in an ambitious and dangerous nighttime expedition – ran the batteries at Vicksburg, floating down the river while sustaining only light losses.

With his Navy now below the city, Grant then ferried his troops across the Mississippi – the largest U.S. amphibious operation until D-Day, 81 years later – and moved on the city from the south. By mid-May 1863, the Confederates were pinned inside Vicksburg, surrounded on all sides. Then it was only a matter of time. On July 4, 1863, Vicksburg surrendered. “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea,” Lincoln stated, upon hearing the news.

4. Jungles Actually Aren’t Impassable: the Fall of Singapore, WWII

The day following the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese launched offensives in Thailand and Malaya. Although British-Indian Army forces were superior in number to the Japanese on the Malayan Peninsula, the British had made a strategic error: they had classified the terrain on the peninsula as largely impassable due to the steaming jungles and jagged hills that characterized much of it. As such, their forces were light on heavy weapons and had very few tanks. The Japanese began a series of offensives, hauling the light mountain howitzers over the hills and snaking columns of their light tanks through the jungles. In this way they were able to outflank and out-maneuver British defensive positions, forcing the defenders to fall back.

In open battle, the British troops were caught at a disadvantage because they could not hold off the Japanese armor. Through the winter of 1941, the Japanese moved down the Malayan Peninsula, occasionally landing troops on the coast to keep the British off balance. By the end of January 1942, the Japanese had isolated the British, Indian, and Australian forces on the island of Singapore. Singapore had substantial shore defenses, but most were facing the sea rather than the Malayan Peninsula. Shore batteries were re-oriented to face the new threat, but since they were mainly equipped with armor piercing shells rather than high explosive, they did not have substantial effect. On February 8, the Japanese opened a massive bombardment on Singapore and then struck the weakest part of the Allied lines. Savage fighting lasted until February 15, when the Allied leaders met to debate the situation: practically out of ammunition, food, and water, they assessed that they could not last much longer. The decision was made to surrender, the largest capitulation of British troops – over 70,000 – in British military history. Singapore was taken and the Japanese conquest continued.

5. Screw your Atlantic Wall, Hitler: D-Day, 1944

At its widest, the English Channel is 150 miles wide; at its shortest, it is only 20 miles wide. And yet, there have only been three successful large-scale invasions across it in military history – subtracting the Vikings, because they went wherever they damn well pleased. The first was in 55 B.C. when Julius Caesar led the first Roman invasion of Briton. The second was William the Conqueror of the Normans who crossed the Channel in 1066 with his army and eventually defeated the Saxons at the Battle of Hastings (As a footnote, the English crossed the Channel multiple times to battle with the French for control of Normandy, with varying results that were eventually unsuccessful – and by eventually, I mean by 1801, because no one does vindictive like the English and French). The next successful cross-Channel invasion was on June 6, 1944. Now that doesn’t mean it hadn’t been tried or thought about before. Napoleon massed barges and ships on the French side of the Channel during the Napoleonic Wars, before eventually scrapping the invasion of England in favor of a dash to Moscow in the winter – a course of action that ended exactly as you would expect. During World War I, the Germans consistently tried to get a foothold on the Channel in order to threaten Britain, but were stymied every time – often in savage fighting. Hitler himself had longed for nothing more than to get his troops onto Old Blighty in World War II, but the heroic actions of the Royal Air Force during the Battle of Britain prevented him from getting air superiority for an invasion. The Royal Navy never lost their grasp on the Channel, which also helped. Like a sulky child, Hitler determined that if he couldn’t have England, then England could never get back to France. He consequently invested a massive amount of time and money into building an extensive network of coastal fortification along the English Channel, dubbed the Atlantic Wall. He then gave it over to his most trusted general, Erwin Rommel, for defense. The Germans expected an attack to be aimed at Calais, at the shortest part of the Channel, although Rommel did make preparations for an attack on the Normandy coast.

In fact, the Allies did strike at Normandy, crossing the 100 miles of the Channel on the night of June 5/6, while also dropping paratroopers, glider troops, and special forces behind the beaches. After only 45 minutes of naval bombardment, the Allies began landing 132,000 troops on five beachheads. Despite the strong German defenses, the varying tides, and the difficulties of coordinating one of the most complex military operations in history, the Atlantic Wall had been breached by the evening of June 6. It was the beginning of the end for Hitler’s Nazi dream.

6. Never Underestimate Crazy People who are Willing to Haul Artillery over Impassable Mountains

This is a maxim that I’m going to claim that I’ve invented, but it has been in practice since the very beginning of warfare. When you’ve got people willing to use ropes and chock blocks to slowly pull heavy weapons over the mountains in order to strike a blow, begin worrying. Because it means that you’ve got a very determined foe. The French didn’t realize this at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, thinking that their base in French Indo-China wasn’t vulnerable to Viet Minh artillery. The Viet Minh proved them wrong by slowly and secretly moving guns into place in the mountains around the base. When the Viet Minh launched their attack on Dien Bien Phu in March of 1954, their attacks were supported by devastating artillery fire. The French were unable to conduct effective counter-battery and Dien Bien Phu was eventually overrun, in a disaster for the French.

A decade later, the U.S. nearly committed the same tactical error at the base at Khe Sanh. The Marines realized the base was vulnerable from the surrounding hills, and established outposts there – resulting in nearly non-stop battles and skirmishes with the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) known as the “Hill Fights.” The U.S. also established multiple fire bases nearby in order to deliver more counter-battery fire to support Khe Sanh. Even these could not stop the nearly ceaseless artillery and rocket bombardment of Khe Sanh during the siege of that base in 1968. Ultimately, the Khe Sanh was not another Dien Bien Phu because the Americans were able to resupply the base far more easily – and allocated significantly more assets than the French had. By one account, nearly as much ordnance was dropped around Khe Sanh by the U.S. Air Force during its existence as was dropped on Japan during World War II, minus the atomic bombs.

Fast forward to the next century, and the U.S. military was once again in combat in a mountainous terrain – Afghanistan. In an effort to place U.S. troops in the line of advance of enemy troops, they constructed combat outposts in these mountainous regions, such as the Korengal and Pech River Valleys. In a pattern we now recognize, the Taliban dragged heavy weapons up steep slopes and over goat trails to target U.S. outposts in the valleys below. Mortars, rockets, and DShK heavy machine guns were used to barrage U.S. positions. American patrols, air strikes, and artillery fire continuously probed for these weapons emplacements in an effort to protect the combat outposts.

“In a fight between a bear and an alligator,

it is the terrain which determines who wins.”

– Jim Barksdale

Military terrain does indeed determine who wins or loses, but it is also the leader who does not assume that terrain is impassable who very often wins.

Enjoy what you just read? Please share on social media or email utilizing the buttons below.

About the Author: Angry Staff Officer is an Army officer who is adrift in a sea of doctrine and staff operations and uses writing as a means to retain his sanity. He also collaborates on a podcast with Adin Dobkin entitled War Stories, which examines key moments in the history of warfare.

Awesome, but it’s unfazed, not unphased. Different words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cerro Gordo springs to mind as well…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Ardennes, perhaps?

LikeLiked by 2 people

A good post, but I have to say that “…scaring the bejupiter out of the Romans” just did it for me. That’s good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great read and thanks for the further reading tip of Battlegrounds!

LikeLike

Great post!

Minor nitpick: there have actually been *four* successful cross-channel invasions since the Vikings — the fourth is in 1688, when William III of Orange landed a Dutch army in Britain, toppled the Stuarts, and installed himself and his wife as monarchs.

LikeLike

I recall Vaguely Hearing about two gents who drove through the Qattara Depression (Bad Desert Place) and told to STFU about it soonest after they’d done it. Why it never occurred to someone to *do* something about it, who knows?

And then, of course, there’s the Golan Heights. Who knew that tanks could go straight up if you asked them nicely?

And as usual, please pardon me if I’ve heard things wrong.

LikeLike

As on eof your crayon eating fans, let me posit this question: since when has the Mass Pike been considered a passable road?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Touché

LikeLike

This is a thoughtful and thought provoking post! great

LikeLiked by 1 person