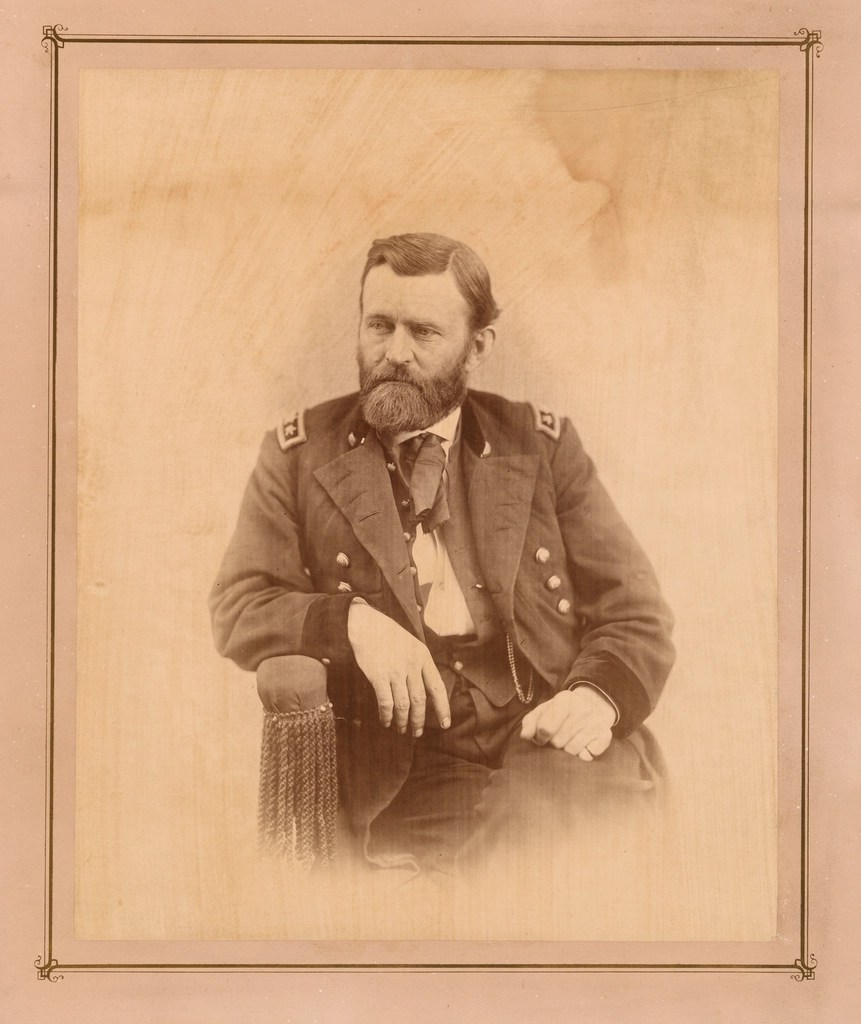

Perhaps no period characterized chaos about the future of the Republic than the years 1866-1868. And perhaps no one individual did so much to save it in those years as the man who had labored so hard to preserve it from 1861-1865: Ulysses S. Grant.

One would think that having put down a rebellion, the United States would be on a path to recovery and strength. Enter President Andrew Johnson. President by virtue of Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson was the worst man at the worst place at the worst time (oh, for an alternate universe where Lincoln kept amiable Mainer Hannibal Hamlin as VP in 1864). As a pro-Union Southerner, Johnson was not only conciliatory to the former self-declared Confederacy but downright magnanimous. And less than enthused about the prospect of abolition, to put it lightly. A dedicated enthusiast of the White race’s dominance in the U.S., Johnson would stand in the way of any civil rights legislation.

Scarcely had the guns stopped firing on the battlefield than Johnson began to show warning signs that the victory won on the field was about to be lost politically. Johnson welcomed former Southern congressmen back to the House – many of whom had just taken off their Confederate Army officer uniforms. As northern and Unionist congressmen watched their recent antagonists resume the seats in the government they had just tried to restore, their tempers exploded. In a simple act of bureaucratic procedure, the clerk of the House refused to read in the names of the Southern congressmen during roll call opening the 39th session of Congress in December 1865. The House remained solidly Unionist and abolitionist.

However, Johnson would not be de-fanged so easily. Even with a solid block of loyal Republicans in Congress, Johnson wielded his veto to try to strike down any civil rights legislation and any bills that would protect Southern Blacks from the “rebellious spirit” of Southern Whites, as George Armstrong Custer (of all people) called it. 1 He also attempted to withdraw U.S. troops from the South, the line of defense for freed people against terrorism, kidnapping, and brutality. Congress halted the withdrawal of U.S. Army troops in January of 1866. The Army was now very definitely in politics. And so was its general-in-chief.

Defender of the Republic (Again)

Ulysses S. Grant would not have described himself as a politician, but as General of the Army, he played a significantly political role. And for the first time, Grant found himself taking an opposite position from the president he was supposed to support and advise. Releasing General Orders No. 3, Grant directed the Army to protect loyal citizens and Blacks in the Southern states not just from physical violence, but from political violence – quietly letting commanders know that they were to obey orders coming from him, not the executive branch. The order directed commanders to protect African Americans from unfair prosecution by state and local courts. Unwilling to publicly challenge the popular general, Johnson let this slide. For now. But he marked that Grant had sided with Congress.

The summer of 1866 was marked by violence: physical, from Whites against Blacks in the South; and political, between the president and congress. As White mobs committed murders, rapes, and atrocities in towns and cities across the South, Congress pushed through the 14th Amendment and extended Federal judicial protection for freed people – all over Johnson’s attempts to veto. As Grant watched the president fight so hard against everything the war had been fought over, he became, as an aide said, “more & more radical.” Most of all, he would not allow the Army to become a “party machine.”2

For his part, Johnson realized that he would not get anywhere until Grant was out of the way. To test the General-in-Chief’s loyalty, Johnson had Grant accompany him on an August political tour of Northern states. Grant grew so disgusted at Johnson’s ranting against the 14th Amendment that he claimed illness and went home early, writing to his wife Julia that he looked upon the president as “a national disgrace.” Johnson openly wondered about using the military to purge his enemies from Congress, asking Grant which side the Army would take in such a trial. Grant sidestepped this by replying whichever side the law was on, while quietly ordering weapons moved out of arsenals in the South. Writing to his old friend and fellow Ohioan Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, Grant confided his worst fears: “we are fast approaching the point where he [Johnson] will want to declare the body [Congress] illegal, unconstitutional and revolutionary.”3

The Banishment to Mexico

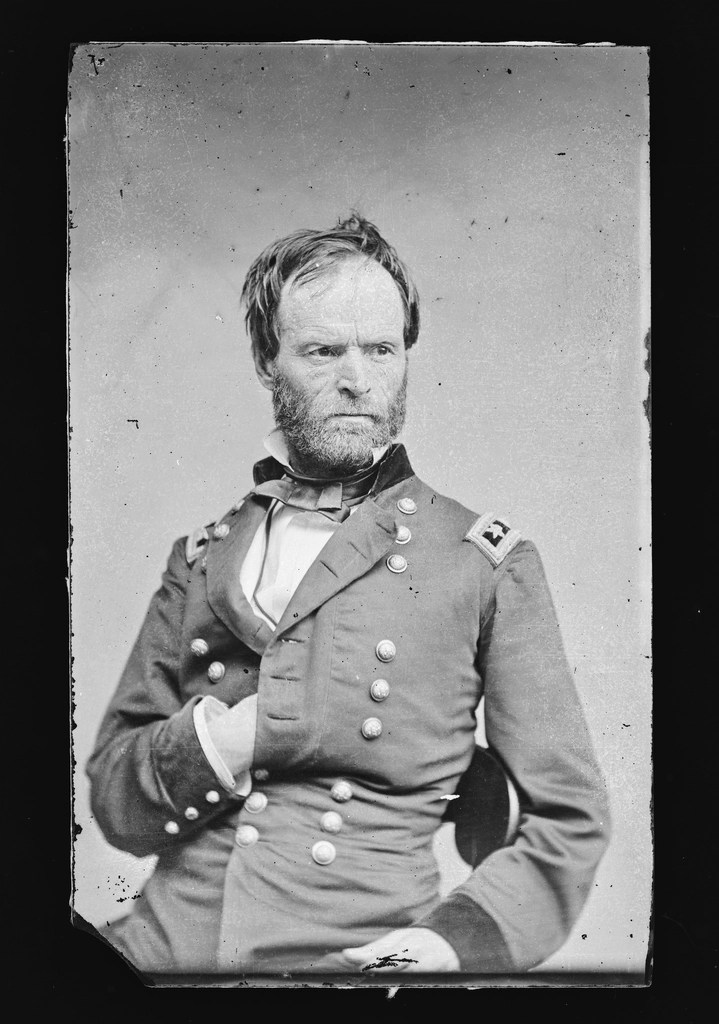

Johnson resolved to get Grant out of the way before the autumnal elections. Governor Thomas Swann of Maryland requested federal troops to oust Republican voting registrars from Baltimore, where the city had just defeated a bill that would have granted voting rights to ex-Confederates. Grant had resisted this request, so Johnson resorted to the age-old method of removing a troublesome subordinate: appoint them to a diplomatic mission and get them out of the country. In this case, Mexico. Johnson directed William Tecumseh Sherman to come east to replace Grant, believing that Sherman would fall into line. Sherman came east, but refused to have anything to do with Johnson. Johnson even promised him the position of secretary of war. Nothing doing. As Sherman is said to have stated about Grant, “Grant stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk, and now we stand by each other.” Once again, he stuck with Grant. Finally, Johnson ordered Grant to Mexico. But there was a problem. Grant refused.

Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman once said of Grant, ““[Grant] habitually wears an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall, and was about to do it.” To say he was stubborn is an understatement. Claiming that he lacked the diplomatic skills for such a mission and that the president would be better served with someone from the State Department, Grant dodged the assignment. Johnson ordered him to do so in a cabinet meeting, which caused Grant to answer, “I am an American citizen, and eligible to any office to which any American is eligible. I am an officer of the Army, and bound to obey your military orders. But this is a civil office, a purely diplomatic duty that you offer me, and I cannot be compelled to undertake it. … No power on Earth can compel me to do it.” Annoyed, Johnson sent Sherman to Mexico and asked Grant for troops in Maryland to “intervene on the governor’s side to prevent violence.” “This,” Grant observed, “would produce the very result intended to be averted.” He refused to send troops but did issue G.O. No. 44., ordering U.S. Army officers to enforce the Civil Rights Act. Johnson and Grant were now in their own conflict.4

Reduction by Promotion

The fall 1866 elections brought another veto-proof Republican majority back to Congress which began to execute Congressional Reconstruction, returning the South to military districts until each state met conditions of equality and adherence to the 13th and 14th Amendments. Congress also passed a rider in the military appropriations bill which removed presidential authority to give direct orders to the Army: all orders would have to go through, or come from, Grant. When in 1867 Johnson’s attorney general tried to reduce the authority of U.S. Army officers; Grant told district commanders that since the opinion did not come through military channels, they were free to use their own judgement.5

When Congress recessed for the summer, Johnson decided one more time to get rid of this troublesome general who kept interfering in his plans. This time, he would get Grant out of the way by suspending Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (another Ohioan who gave Johnson constant headaches via stubborn resistance) and replacing him with Grant ad interim. A reluctant Grant acceded, possibly to keep another more compliant person from occupying the position.

But the fall 1867 elections brought more Democrats into office and a surge of terrorist groups in the South, such as the Ku Klux Klan. Johnson moved swiftly to consolidate power, firing generals heading military departments. Notably, he fired Sheridan, further alienating Grant and inflaming the situation in the South where violence levels grew. As Maj. Gen. John Pope left command of the district encompassing Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, he noted to his replacement, Maj. Gen. George Meade, “the Rebellion is as active & so far as the people of this Dist. are concerned, nearly as powerful as during the War.”6

Congress entered the fray in January of 1868, setting the stage for Grant’s last battle with the president he served. Congress ordered Stanton’s immediate reinstatement. Johnson refused. Grant, then, was left with the thorny choice of disobeying the Senate and violating the Tenure of Office Act, or directly opposing his president. It probably comes as no surprise that Granted handed over the keys to the War Department to Stanton. This utterly enraged Johnson, who went off on Grant in a cabinet meeting. Johnson then tried Sherman again, offering him command of a special division to be headquartered in D.C. – a thinly veiled threat to Congress. A disgusted Sherman headed west. Johnson then gave the same offer to Virginian Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas. He should have known better than to try to coopt a man who broke from his family and state to stay loyal to the Union in 1861. Thomas turned him down. An infuriated Johnson then fired Stanton, but that cantankerous cabinet member locked himself in his office and refused to come out. This was the last straw, and after three days of Stanton confinement, the House impeached Johnson.7

Conclusion

Civilian control of the military is a bedrock of American democracy, repeatedly enforced by Washington during the Revolution and embodied in law thereafter. Could any general other than Grant have gotten away with this resistance, and could Grant have done it if it had been any president other than Johnson? We will probably never know. Grant was a national hero and Johnson was vilified by half the country. The era was one of repeated constitutional crises, so gray areas were more common. What we do know is that Grant’s steadfast devotion to civil rights and stubborn commitment brought him to national political attention, and he was on the ballot as the Republican candidate for president in 1868. His nemesis, Johnson, did not even get the nod from his own party and did not appear on the ballot.

Yet another opponent who lost to Grant.

Sources:

- Robert Wooster, The U.S. Army and the Making of America: From Confederation to Empire, 1775-1903 (University of Kansas, 2021), 204. ↩︎

- Wooster, 210. ↩︎

- Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site, General Grant Refuses President Johnson’s Diplomatic Request, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/general-grant-refuses-president-johnson-s-diplomatic-request.htm; David O. Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (Simon & Schuster, 2010). Ivan Perkins, Vanishing Coup: The Pattern of World History since 1310 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013). ↩︎

- Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site, General Grant Refuses President Johnson’s Diplomatic Request; Wooster, 212. David Priess, “How a Difficult, Racist, Stubborn President Was Removed From Power—If Not From Office,” Politico (Nov. 13, 2018), https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/11/13/andrew-johnson-undermined-congress-cabinet-david-priess-book-222413/ ↩︎

- Wooster, 215. Priess. ↩︎

- Wooster, 215-217. ↩︎

- Ulysses S Grant National Historic Site, Ulysses S. Grant is Appointed Secretary of War Ad Interim, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/ulysses-s-grant-as-appointed-secretary-of-war-ad-interim.htm; Wooster, 217-219. ↩︎

Enjoy what you just read? Please share using the buttons below.

The opinions represented here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

You must be logged in to post a comment.