Take heart, all you who grow unsettled at the time of year where the narrative of friendly Pilgrims and American Indians is spread around to make us feel good about a brief moment in American history before everyone started killing each other. Thanksgiving as a national holiday is actually about another time when everyone was killing each other: the Civil War (cue the Ashoken Farewell).

The year was 1863. It had begun inauspiciously for the cause of liberty and union, with Grant’s western army hung up around Vicksburg on the Mississippi River and the main eastern army stuck in the northern Virginia mud. All that changed by mid-year, with the twin victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg. By the fall, the Confederacy was split in two and its brief offensive towards Chattanooga had been halted and was breaking. Lee was pinned back in Virginia with his army and would never leave it again (if ya can’t win a battle outside Virginia, I don’t think they get to call you a “great” general). The U.S. Navy – with its new ironclads – continued to encircle the rebellious states and roam the navigable rivers spreading the Stars and Stripes deep into the interior. The war was not yet over, nor yet won, but President Abraham Lincoln thought he could just begin to see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Accordingly, in October – after some goading by Sarah Hale, the editress of Godey’s Lady’s Book – he announced a day of Thanksgiving set for the last Thursday of November. This was not a new concept; governors had been declaring days of thanksgiving – or, alternately, prayer and fasting, depending on the vibe – since the colonial era (ex: “it is 1759, we still have not taken Quebec, it must be the result of our sins, so I declare a day of fasting” – or, it is 1760, “we have taken Quebec, God is no longer mad at us, I declare a day of Thanksgiving,” etc, etc). Governors over the years set their own annual Thanksgiving days for their states, but Lincoln’s proclamation would change this. He was proposing a single national day to celebrate. A national day of thanksgiving was not an anomaly; Washington as president had declared national days of Thanksgiving. Lincoln had just declared a national day of Thanksgiving as recently as August. But setting a single day, November 26 (or the last Thursday in November), for the whole country to celebrate in perpetuity was something new.

Lincoln’s proclamation – written by Secretary of State William Seward – asked Americans to think beyond the current conflict to find gratitude for their harvests, the fruits of their industrial labor, continued immigration which caused the population to expand, and for the “advancing armies and navies of the Union.” It also asked people take a portion of their bounty to think of those afflicted by this conflict: the widow, the orphan, and the wounded. In all, not a very controversial proclamation – especially considering his proclamation that had gone into effect on January 1 of that year, asserting that freedom for the slave was to be a war goal, as well as union.

The Thanksgiving Controversy

Not a controversial proclamation – but because it was from Lincoln, and this was wartime, and in the heavily divisive mid-19th century where newspapers were either Republican or Democrat, the proclamation immediately drew the fire of Lincoln’s detractors. “We do not like the proclamation and may as well say so,” grumbled the editors of the Monmouth Democrat on October 8, 1863. Why? Because it trampled on the right of the states to set their own Thanksgiving, of course. Like conscription, the editors charged, it was another example of government overreach. They also did not like it because of “ambiguous phrases in it which have a very unpleasant odor.” The line they took umbrage with was “a large increase of freedom,” which they used as an opportunity to descry emancipation and accuse Lincoln of imposing shackles on the white man. Just normal 19th century stuff. “We will not observe it,” the editors huffily declared.

Many people asked what on earth the United States had reason to be thankful for in the midst of the bloodiest war in its history. To that, the Lewiston, Maine Sun-Journal answered on Nov. 25, “If ever a people had cause for Thanksgiving for the Providences of a year, that people is the people of the loyal United States, for those of the past year. For Emancipation, for Victory in the field, for plenteous harvests, for countless biessings, we have great cause for thanks to Al-mighty God.”

The New York Herald did not directly pounce on Lincoln’s proclamation as it normally did beyond pointing out on Oct. 5 that traditionally Thanksgiving had grown to be a state prerogative and that presidents as recent as Zachary Taylor had demurred to interfere with the rights of the states. Reading in between the lines, however, the inference is clear: Thanksgiving is just another example of executive tyranny. The New York Tribune fired back against what it called this “copperhead organ” on Oct. 7 with a “well actually” of their own, reminding the Herald that George Washington set a national day of Thanksgiving in 1795. So there, the editor seemed to say.

An unknown ranter to a Welsh paper wrote, “Mr. Lincoln will be cursed by every Governor of a State that has been in the habit of getting up its own thanksgivings for the past 200 years. To give thanks is a State right. It has always been conceded to the Governors of the States that they should issue their own thanksgiving proclamations, and select their own time for the slaughter of turkeys.” (Pontypool Free Press, Oct. 24) Clearly, Lincoln could do little without causing controversy.

The Detroit Free Press went on the attack on Thanksgiving day itself, jabbing at each line of the proclamation. Quoted in many Democratic newspapers – and lampooned in Republican papers – the editors lambasted the administration’s conduct of the war and the cause of the war itself. They attacked abolitionists, decried the draft, blamed immigrants, caterwauled that it was unpatriotic to give thanks when so many were suffering, and stated that the only thing to be thankful for was that each day “brings us nearer to the close of Lincoln’s administration.” Lincoln’s proclamation, they stated, was bordering on the unconstitutional. Republican papers then asked where in the Constitution did it describe presidential holiday-making powers, and the acrimonious debate roared on until the next controversy. Plus ca change, and all that.

Some papers did a fact check on Lincoln and Seward’s claim that the population was expanding, in spite of war. They found it was true. New York reported 160,000 immigrants through its port alone that year. The Brunswick Times Record in Maine prophesied on Dec. 4 “Notwithstanding the fearful loss and embarrassments of the war, we believe that the next census of the United States will show a population of forty million freedmen – including, of course, the States and people of the South, who will all then be back in the Union, and will all have taken the oath of allegiance, except Jeff Davis and other rebel chiefs, who will either have taken refuge in Mexico or in Hades.”

State Proclamations

Beyond the quibbling, governors went along with the president and issued proclamations of their own for Nov. 26. They mostly echoed Lincoln: give thanks for our blessings and look after those afflicted by the war. Each tended to add their own little piece of flair, however. Gov. Horatio Seymour of New York reminded his constituents that this war was brought about by rebellion caused by the “wickedness, folly, and crimes of men” (NY Herald, Nov. 11, 1863). New Jersey’s governor prayed for a “change of hearts in our enemies” (Holmes County Farmer, Nov. 26). Gov. Tod of Ohio gave thanks “for the unwavering determination that the enemies of our dear country, both at home and abroad, shall be discomfited.” (Bryan Press, Oct.29) Ohio, afflicted by the antiwar “copperheads” personified in Clement Vallandingham, had excellent cause to wish for an end to the enemies at home. Minnesota gave thanks for the for the “extension of the area of human freedom,” brought about by the war (Rochester Republican, Nov. 18). Illinois added, “Let us thank God that in spite of foreign hatred and plotting treason, and the fearful shock of arms we still have a country, and the glorious hope of a country laden with unspeakable blessings for our children and our children’s children” (Warren Sentinel Leader, Nov. 12). Across the loyal states, each had special cause to find gratitude in time of sorrow.

Pennsylvania’s Gov. Curtin had special cause to give thanks in 1863, as he wrote, “And for the crowning mercy by which the blood-thirsty and devastating enemy was driven from our soil by the valor of our brethren, freemen of this and other States” (Waynesboro Record, Nov. 13). Just days after his Thanksgiving proclamation , Curtin was present at the dedication of the first national cemetery in the United States, at Gettysburg. It was here that Lincoln gave new meaning to the war – calling it a “new birth of freedom” – and rededicated the United States to this cause.

Therefore, it was fitting and proper that it should be a freedman who read Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamation to the United States expats in England. According to The Caledonian Mercury on Dec. 17, 1863, 150 Americans in London came together at St. James’s Hall to celebrate Thanksgiving and read the president’s proclamation – including the American ambassador to England. The man selected to read the proclamation was Mr. Selma Martin, “a coloured man, a fugitive slave, who…became the mouthpiece of the President of the United States in offering thanksgiving to God for the blessings showered down on America.”

Truly, the new birth of freedom was cause for thanksgiving, and continues to be an inspiration to all who seek to enlarge the meaning of the Declaration’s promise of equality and rights. In the previous year’s thanksgiving proclamation for the state of Maine, Gov. Washburn had made special mention of the extension of freedom via the Emancipation Proclamation. When the proclamation was read to one of the state’s regiments in the field, it greeted the sentiment with rousing cheers (Lewiston Sun-Journal, Jan. 3, 1863).

As you sit down with your family, let us remember the true meaning of Thanksgiving: the victories of the U.S. Army and Navy, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the aspirational nature of our Republic.

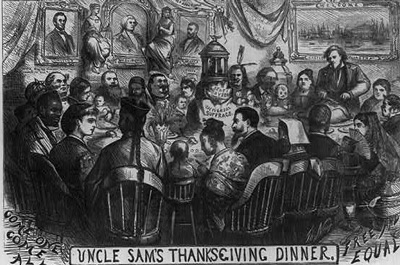

This Thomas Nast cartoon, titled, “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner” was published in 1869, and looks hopefully to a diverse but unified America.

(Library of Congress image)

Enjoyed what you just read? Please share using the buttons below.

Opinions expressed herein are those of the author’s and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Department of Defense.

Cover image: Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly, Nov. 26, 1864

A note on historiography: much of this post was written off of research conducted from newspapers, which have many issues inherent to them. At first glance, they may seem to represent a given group. On closer examination, they represent the views of a niche group. Admitting and recognizing this, they can be used to show snapshots of public opinion in a certain time and place.

You must be logged in to post a comment.