The other day I went and stood in front of the new section of the World War I memorial in Washington, DC and looked at it. Memorials are meant to make you feel something. I felt nothing. I felt nothing when I looked at the figures. So I looked at the equipment. I looked at the uniforms. I looked at the faces. I looked at the setting. I still felt nothing. I stepped back and looked at it holistically. Then I went up close and looked at each detail bit by bit, and then I finally felt something. I felt anger.

I felt incredibly angry at those who thought that this was an homage to the World War I generation, at the people who believed that these figures and the way that they were cast symbolize how a nation felt after a massive bloodletting on a scale which we have yet to truly comprehend. As if this could provide meaning for one of the most misunderstood wars in U.S. history. And as if this could bring Americans closer to the silent WWI generation.

Memorials are tricky things because they are supposed to tell us something about ourselves and in the process we are supposed to see part of ourselves in that memorial. Every monument is meant to make us feel something. It might be sadness. It might be reverence. It might be that all you’re supposed to feel is just anything at all. Anger is probably not what those who created this monument meant to evoke, but it is what they intended to evoke that makes me so angry.

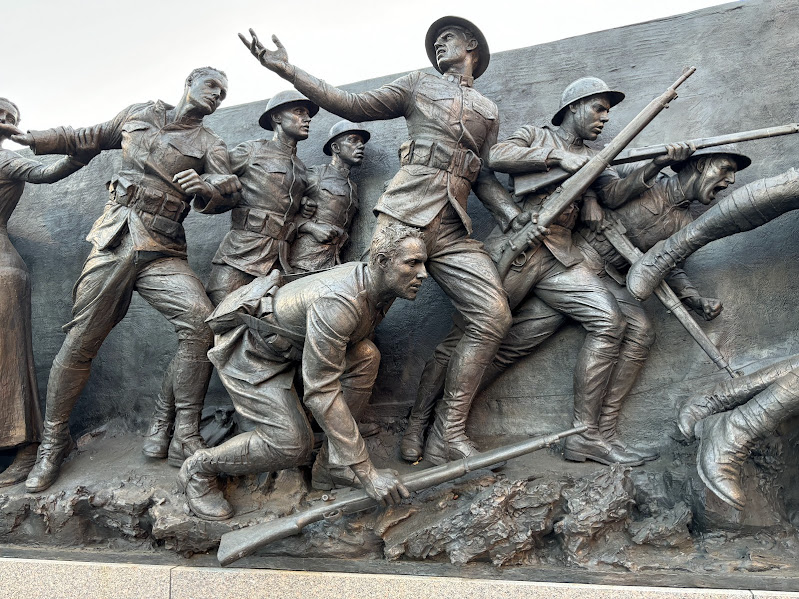

The figures on the memorial do not depict the American actors of World War I; they depict an idealized bastardization of memory. They are all heroic. They are all energetic. They are all useful. They are all manly – even the women are manly. Everyone is their best self. No one is afraid. No one lacks the courage to go forward. Everyone goes forward together, even those who were not allowed to go together because of race and gender. If we want to be truly honest, we need to address the problems inherent in memorialization that literally whitewashes our shortcomings as a nation. On the monument, Black and White soldiers fight next to each other – they walk arm and arm to war, something they were literally not permitted to do by the United States government. In short, it is an image of a generation that did not exist. Were World War I veterans to come back and look at this monument, the doughboys would not see themselves there.

Comparing the World War I memorial to those war memorials already on the Mall creates an interesting problem set. The Vietnam memorial stands on its own: unique, stark and tragic, somber and powerful. Across the reflecting pool, the figures of the GIs on patrol for the Korean conflict memorial are haunting and somehow otherworldly, but allow us to feel something human in their faces. There is uncertainty. There is courage. There is humanity. Then, of course, there is the World War II memorial. A monstrosity of marble and iron and water so large that it doesn’t really make an impact on you, which I suppose is a message in and of itself.

If you go all the way down the Mall to the Capitol you will see another memorial that is perhaps not for a war, but for a nation. In front of the Capitol you will see the monument to General U.S. Grant, flanked on either side by statuary representing soldiers of the US armies that put down the rebellion from 1861 to 1865. On one side, you see the cavalry, and the other the artillery. Neither of these sculptures shows anything other than the plodding brutality of war. With the cavalry, yes, one rider charges forward, sword up, raised face, shouting, leading a charge. The others are focused, intense, frightened. One man is thrown as his horse goes down – his hand reaches out in an achingly life-like way towards the onlooker as he and his horse plunge into the mud. This is not glory. This is war.

On the other side, gunners lash their team of horses to haul forward and an artillery piece. The drivers and men are hunched forward into what appears to be a cold and driving rain. They are miserable. It is not glorious. It is war.

Above them, their commander sits firmly on his horse – not a horse that is rearing in action, but one as immobile as its rider. It is a horse that looks south as its rider does, stolid and fixed in his saddle, hunched against what might be a cold Virginia rain. They appear immovable as they gaze towards Richmond and the end of the war. It is not glorious, because war is not glorious.

And this is a principal issue with the World War I memorial. For the doughboys themselves, the war was not glorious. They were of the most sardonic sarcastic generations of American soldiers to go off to war in our history. They were young. They were eager for an adventure, but they were not glorious. They came home hardened by their experiences. The war changed them and it changed us as a nation. There was no heroic American decade following World War I. Instead, we pushed away from the world stage, we turned inward. The world moved on without us. It was not heroic. It was not glorious.

From a purely technical and tactical standpoint, the memorial stands as a mockery to what Americans think they know about World War I. It tells the story of American riflemen who single-handedly won the war, the Pershing fever-dream of what he thought would turn the tide of war. It does not show the vast quantity of supplies shipped across the Atlantic, the thousands of artillery tubes pounding the Western front, the machine gun chatter, the roar of trucks, the whine of airplanes, the vast and powerful industry of a nation thundering to life. World War I was the first time the nation fully mobilized for war and fought it on an industrial scale. But you would not know it from this monument.

This monument idealizes a fictional soldier, one who never existed. “We leave you our deaths. Give them their meaning,” states an excerpt on the back of the monument from The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak by Archibald McLeish. While it is perhaps ironic that the opposite of the monument cannot meet this appeal, it is important to remember that memorials seldom capture the nature of a thing. They are designed to make you feel something. In this, the new addition to the national World War I memorial was, unfortunately, successful.

Enjoy what you just read? Please share using the buttons below.

The opinions represented here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

You must be logged in to post a comment.