So there I was the other day, just minding my own business and falling down some social media algorithm-caused rabbit holes of a Saturday night, like ya do, when I came across this image:

Now, for those of you who are war monument nerds like myself, you may have recognized this as being cast in the image of the famous “Lion of Lucerne,” in Switzerland, which was dedicated in 1821 as a memorial to the Swiss guards who died in the 1792 fighting around the Tuileries during the French Revolution.

The actual sculpture is gorgeous and moving, drawing in over a million tourists per year – but like all war memorials, it is not without controversy. The lion’s paw rests on the shield emblazoned with the lilies of monarchical, Catholic France, which was not something a lot of protestant, republican Swiss were overjoyed to be tied to. Nor were they committed to such a monstrous monument being nearly entirely bereft of Swiss imagery. Suffice to say, it was controversial as soon as it was dedicated, with protests occurring the day of the dedication and brawls between liberals and conservatives in the neighboring town.

As an aside, this is always a good time to remember that memorials are nearly always about making a statement and should be viewed as such. They are almost never neutral. Nor do they exist to “teach history.” They are designed to make you feel a certain emotion, and you should always look at them with this in mind.

Now, this was not the first knock-off/tribute to the Lion of Lucerne I had seen in the U.S. Years ago, while on a visit to Colby College in Waterville, Maine, I was stunned by the marble “Weeping Lion” on campus.

In 1866, the trustees of the college met to determine a suitable memorial for the twenty men of the college who had died during the Civil War (prior to the war it was known as Waterville College; one of its noted alumni was the U.S. general Benjamin Butler, who has a recent bio that is well worth the read from Colby’s Dr. Elizabeth Leonard). It was apparently Dr. Henry S. Burrage – who is pretty much responsible for writing down half of Maine’s history as their first state historian and who was himself wounded in action during the Civil War – who suggested modeling their memorial off the noted Lion of Lucerne, giving one an idea of just how far this sculpture’s impact had spread. Working with Irish-born Boston-based sculptor Martin Millmore, Colby science Prof. Charles E. Hamlin (of no direct relation to the vice president of that last name) raised the necessary funds and the monument was dedicated in 1871.

A Brief Aside

The names on the monument give a fair history of the Civil War – men killed in battle, by accident, dying of disease, or dying of wounds. George C. Getchell served in the famous 20th Maine until he volunteered to serve as an officer of United States Colored Troops a month before Gettysburg. He died of yellow fever with the 81st USCT in New Orleans in 1866. William S. Heath enlisted with his brother Francis in 1861. Prior to the war, he wrote the following poem, which illustrates the strong ties the Revolutionary generation had on New England families:

William Heath was killed in front of his regiment in fighting around Gaines Mills, Virginia in 1862. His brother Francis was wounded at Gettysburg, helping repulse Longstreet’s attack on July 3d.

Confederate Lions

By 1880, the Swiss stone feline’s fame was growing, as America’s favorite tourist, Mark Twain, dedicated a long paragraph to the Lion of Lucerne in A Tramp Abroad, ending with, “The place is a sheltered, reposeful woodland nook, remote from noise and stir and confusion—and all this is fitting, for lions do die in such places, and not on granite pedestals in public squares fenced with fancy iron railings. The Lion of Lucerne would be impressive anywhere, but nowhere so impressive as where he is.”

American sculptors thought otherwise, because nearly two decades later, in 1894, the 2d copycat showed up – this time, in Atlanta, Georgia. And whereas the Lion of Colby had been non-controversial, this lion aimed to imitate the original by sending a very clear message.

The Lion of Atlanta could not have been constructed or dedicated in 1871, as the Colby lion had been. As Dr. Caroline Janney points out in her outstanding and monumental – no pun intended – book Remembering the Civil War, Confederate memorialization remained in the shadows during Reconstruction (1866-1876). With U.S. troops occupying the formerly rebellious – and sort of still rebelling – states, women took up the role of memorialization in cemeteries while former Confederate men remained in the background. Not that the men were exactly silent, since plenty of them actively fought Reconstruction by keeping Black men from the polls, intimidating Unionists, and terrorizing Black families. But with U.S. troops present, violence was somewhat contained. By the 1890s, however, with Reconstruction long over, state legislatures and local governments were purged of Black politicians, often violently and bloodily. White southern nationalism was allowed to come back out in the open. Which is what the Lion of Atlanta was all about.

The dedication ceremonies in front of a crowd of thousands were in the theme of the Lost Cause – the post-war southern narrative that stated that the southern states were doomed from the first because of the disparity of numbers, that the war was not about slavery but that slavery was a beneficial institution for all, that secession was legal and justified, and that one southern soldier was worth three northern soldiers. The Lost Cause was crafted to help White southerners cope with a devastated economy, a feeling of a loss of manhood, and a destroyed social system. It was also a series of lies; White Confederates had no problem upholding slavery before and during the war, the war settled the legality of secession, and northern soldiers were just as competent soldiers as their southern counterparts. Not to mention, lots of southern soldiers fought for the United States. Woops.

As if trying to fill up a Lost Cause bingo card, one speaker at the dedication said, ”It was not for want of a righteous cause that they failed; it was because they were overwhelmed by the forces that had the power to draw upon the rest of the world in their efforts to crush them. Why this righteous cause should have failed, God in His wisdom only knows.”

Another orator waxed eloquent about how the “snowy Alps of Schwytz” surrounded the original Lion of Lucerne, which looked down to “soften the whole scene with their perpetual white,” and how the Lion of Atlanta was “carved from Georgia’s purest, whitest marble.” As you can read for yourself at the above link, he proceeds to go off on a very long rant about how the Confederates were also fighting for union, how they have not created a “new south” but “rehabilitated our grand old south with a new life,” and how armed rebellion to was actually quite patriotic.

One orator called this monument to the Confederate unknowns buried in the cemetery the “southern Mecca.” Another compared the fallen Confederates - and the Confederate cause – to that of Jesus Christ, who died for his people. Thus, the Confederacy was never defeated in this worldview, but born anew in a messianic fashion.

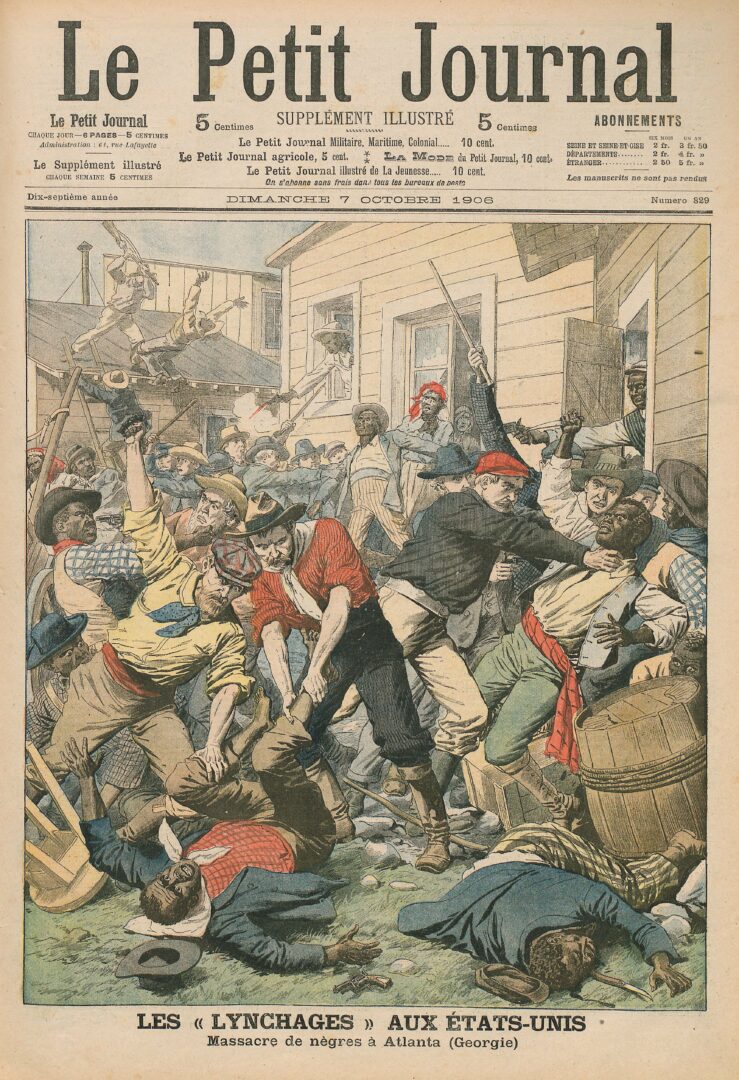

It would all be rather tiresome and blasé, if this were not all the groundwork for Jim Crow laws and the suppression of Black Georgians, which broke out into a full-blown massacre in Atlanta in 1906. Alarmed at unsubstantiated rumors of Black violence against White women, mobs assembled and ransacked Black business, neighborhoods, and modes of transportation.

The resulting violence killed from 25-40 African Americans, depressed Atlanta’s Black community and business, and contributed to restriction of Black suffrage in 1908. The Lion of Atlanta stood as a permanent display of white supremacist authority in the city’s memory.

Almost as if in response to the Lion of Atlanta and its ties to White Christianity, W.E.B. DuBois penned his exceedingly powerful, “A Litany of Atlanta,” in 1906. Several lines run as follows:

“Sit no longer blind, Lord God, deaf to our prayer

and

dumb to our dumb suffering. Surely Thou too art

not white,

O Lord, a pale, bloodless, heartless thing?

Ah! Christ of all the Pities!

Forgive the thought! Forgive these wild, blasphemous

words. Thou art still the God of our black fathers, and

in

Thy soul’s soul sit some soft darkenings of the evening, some shadowings of the velvet night.

But whisper—speak—call, great God, for Thy silence

is

white terror to our hearts! The way, O God, show

us the way and point us the path.

Whither? North is greed and South is blood; within,

the

coward, and without, the liar. Whither? To death?

Amen! Welcome dark sleep!“

One of the orators at the dedication of the Lion of Atlanta said, “these [monuments] shall remain just here for all time, to tell the story of the men buried here, who died for the south and in defense of Atlanta.” In 2021, the sculpture was removed, as protestors targeted it as a symbol of the white nationalism and violence that had killed George Floyd.

The same year as the Atlanta massacre, the third American lion made its debut, this time in Missouri. Erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, it was placed at the Missouri state home for Confederate veterans at Higginsville – today, the Confederate Memorial State Historic Site.

The irony, of course, is that Missouri never seceded from the U.S. Nearly three times as many Missouri men served in the U.S. Army as did in the Confederate Army. Yet for all this, organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy sought to spread the Lost Cause further than the original cause ever had. During the dedication remarks, the main speaker underlined why this monument was important: “There are only a few [Confederate veterans] now, and it becomes the duty of their sons and daughters to demand for them an honest history to make their remaining days more pleasant, to show them by the reverence we have for those have gone before the reverence which we will have for them when they go.” Because the monument was being dedicated at a soldiers’ home, there was little controversy at the time – unlike a proposed Confederate monument in St. Louis that year, which was met with outcry from many Union veterans and other Missourians. Just as in 1906, there has been little outcry today about the Lion of Higginsville.

Why the Lions?

Out of all of this, we are left wondering as to why there are three – and who knows, possibly more – American lions modeled off the Lion of Lucerne. One can almost understand the Confederate perspective, given that it is a monument which honors bravery in defeat. It certainly seemed to capture the imagination of the Lost Cause. The Colby lion remains a puzzler; it is beautiful and noble, yes, but those men did not die for a cause that was “one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse,” as Ulysses S. Grant wrote of Confederate motivations in his memoirs.

The idea of memorializing dead versus memorializing a cause is one which bedevils us to this day. If we say that we want to honor bravery and valor, that can get troublesome, as there were plenty of brave and valorous Nazis who died for a horrific cause. Can the dead be removed from the cause they died for? Those who protested the original Lion of Lucerne in 1821 certainly did not think so. War, memory, cause, and service will continue to be points of contentious debate for generations to come. Looking at how cause mixes with memorialization and memory, we can begin to understand some of the inequities in our own history and hopefully avoid those missteps in the future.

Enjoy what you’ve just read? Please share on social media using the buttons below.

Views expressed in this piece are the author’s own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army or Department of Defense.

Cover image via the author

You must be logged in to post a comment.