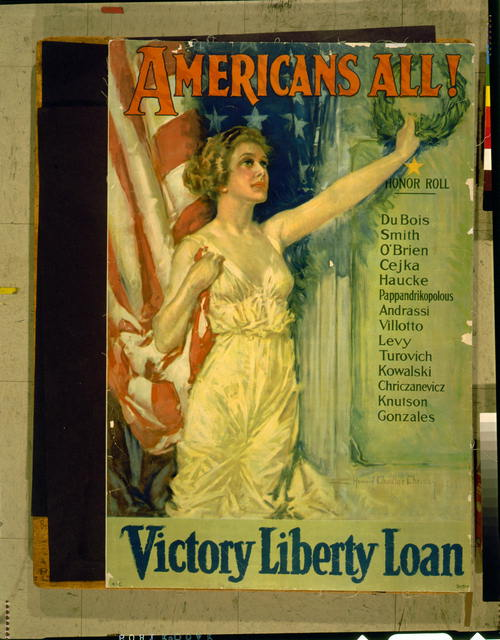

In the woods of northeast France, a group of American artillery officers watched their olive drab-clad batterymen set up their tents in a peaceful glade. It would be the last such quiet the battery would experience for some time. It was summer 1918, and the men of the 305th Field Artillery were going to the front the next day. As the quiet murmur of voices filled the evening air, Lieut. Charles Wadsworth Camp reflected on the historic nature of what was happening: “The National Army was a good deal of an experiment: it contained every type, race [except African American, the Army remained segregated], and temperament. Had its brief training fused these uncongenial elements into a serviceable whole?”1 The 305th was part of the 77th Division, the first division of the National Army to see the front lines. And as Camp (whose daughter, Madeleine L’Engle would go on to far greater prominence as a writer) mentioned, the National Army was a good deal of an experiment.

For generations, the United States had fought its wars relying on states to fulfil quotas of volunteer regiments. These tended to be more or less homogenous units, recruited from the same town or county, with men of similar ethnic and religious backgrounds. With the entrance into World War I, the U.S. Army decided on something new. To augment its Regular and National Guard divisions, the Army would rely on the draft to create new combat divisions filled with inductees from all across the United States. While divisions would still have a regional flavor – the 77th, for example, was from New York City – they would be a hodge-podge of Americans. It was, as Camp would recall, watching a Chinese-American member of a battery ride the lead horse past a reviewing stand, the “unconscious pride[,] the democratic, the universal power of our army.”2 The question, of course, was if you could meld this diverse mess of different ethnic, religious, racial, and cultural backgrounds into a cohesive fighting force to oppose a highly homogenous opponent. Indeed, the National Army was almost a pointed jab at the stratified and warrior-class-focused Prussians who formed the core of the Imperial German Army. German citizens were required to yield the sidewalk to Prussian officers, such was the grip of the warrior culture on the recently unified Germany.

And here came these damned Americans, with their battalions of Poles, Lithuanians, Italians, Cherokee, Irish, WASPs, Cantonese, Germans, and Russians, ranging from families who could trace their American ancestry to a time when Europe was barely a thought to those who were just off the boat. Who did they think they were?

Would it work, was the question on everyone’s minds. It surely couldn’t work. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was disintegrating, in part due to too many ethnicities and nationalities crammed into one government. But as the American divisions were fed into combat through the Spring, Summer, and Fall of 1918, the answer came back: yes. Like their Regular and National Guard counterparts, they all had their bloody and messy first battles. The 77th had the “Lost Battalion,” debacle. But even then, the unit did not break apart or panic. They held on until relief showed up. They began to learn and adapt. By the Armistice on 11 November, the American Expeditionary Force – which had barely existed one year prior – had defeated the would-be supermen. The disdainful Prussian officers had been humbled by the unlikely coalition of immigrant kids from the Bronx and Philadelphia, from farmers around St. Paul and Des Moines, and from Lakota and Navajo from reservations.

Tactical Strength

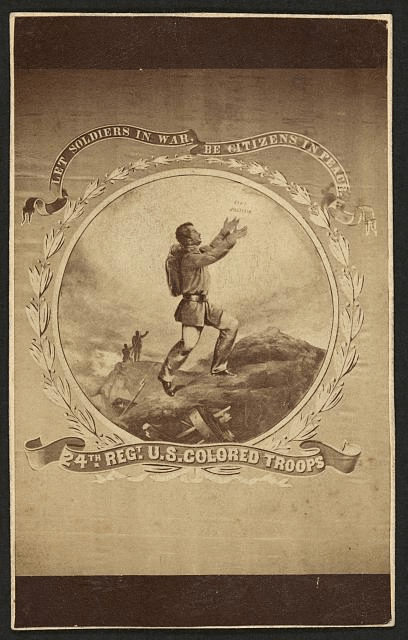

This is not an anomaly in American military history. In 1781, as the French and Americans made their near-miraculous link-up at Yorktown, French Army officer Jean-Baptiste-Antoine de Verger left a brief sketch of his impression of the Continental Army. In the sketch of four soldiers are well-accoutered Continental regulars, a rifleman in a hunting shirt, and a Black light infantryman. Another French officer noted that it seemed as though a quarter of the army outside Yorktown was made up of people of color. Washington had taken command in 1775 with very regional views on race. A Virginian holder of enslaved peoples, Washington ordered his New England regiments to discharge all people of color. Being contrarian New Englanders, they mostly ignored him. As the war dragged on, and as White volunteers came in fewer and fewer numbers, and as Black soldiers continued to distinguish themselves, Washington changed his mind. He needed good soldiers. And as a White private in the 5th Massachusetts wrote after the war of the four Black soldiers who served with him in his company, “They were good soldiers.”3

A French staff officer at Yorktown perhaps put it best, observing in wonder Washington’s motley Continental Army: “It is incredible that soldiers composed of men of every age, even children of fifteen, of whites and blacks, unpaid and rather poorly fed, can march so fast and withstand fire so steadfastly.”4 Out of such beginnings are we made.

Since 1783 and the end of the Revolution, United States society has struggled with the idea of who should serve in the armed forces, and why. The arguments are usually entirely unconnected with the realities of military service and instead focus on social norms, or the perception that the military is being used as a vehicle of social change. It is expediency of the dire hour which usually causes Americans to stop wringing their hands and realize that strength lies in diversity.

It was this expediency that in 1917 led the U.S. military to look past the conventional prejudices of the time against women serving in uniform to find the answer to a pressing problem. Modern war brought modern problems. The telephone now played a major role in war, from the strategic communication between Entente generals and politicians down to the tactical communication from the frontline trench to the artillery battery. Telephone switchboard operators controlled the pace of communications, and thus the fighting. For the novice U.S. forces, General John Pershing wanted the very best operators the nation could provide. They had to be unerringly fast, mostly bilingual in French and English, and ready to go to France at once. Men did not hold this qualification – women did. Bypassing and changing regulations, against the prejudice of the president, the secretary of war, and even Pershing, the Army brought on hundreds of women operators and placed them in the Signal Corps. Stateside and in France, these women controlled the pace of the war. Operating far forward during the offensives, women kept the lines open even under German shellfire. The “Hello Girls” as they were called, had to wait decades for their service to actually be recognized, but their story stands as an example of American strength through diversity.5

These days, it can be confusing to think of ethnicities as being divisive. Yet, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, ethnicity and country of origin made Americans suspicious. Nativism was alive and well at the time of the Civil War. Had the Republican Party not pushed the nativist, America-First Know-Nothing Party aside in the elections of 1856 and 1860, the U.S. Army might have been deprived of some of its best recruits: German-Americans. Flooding into the country from 1840-1855, over 100,000 refugees from the failed revolutions of 1848 and 1849 found new homes in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, western Virginia, Missouri, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Iowa. Mostly middle-and-upper class, educated, skilled, and liberal, these emigres had risen up for the right of self-determination and free thought. Finally defeated by the force of the Prussian army, the military, political, and philosophical leaders of the revolution fled to escape prison and death sentence. And they brought their ideas concerning liberty with them. Being largely anti-slavery, this group enlisted into the U.S. armed forces en mass between 1861-1865, making up over one-tenth of the army. It brought men like August Willich, failed Baden revolutionary commander who once challenged Marx to a duel for being too conservative, and who at Shiloh put his men through close-order drill to steady them under fire. Men like Viennese Jew August Bondi who, after failing in his ordeal as a teenager student-soldier, fled to America with his family, rode with John Brown, and subsequently fought in a Kansas cavalry regiment.

Or Hermann Lieb, from Switzerland, who – while studying in Paris in 1848 – joined the revolution as part of the Garde Mobile, a part of one of the few successful revolutions that year. Living in Illinois at the outbreak of war in 1861, he enlisted as a private in the 8th Illinois Infantry, rising to major by 1863, when he accepted command of the 9th Louisiana Regiment (African Descent). In command of Black troops at Milliken’s Bend during the 1863 Vicksburg Campaign, Lieb’s troops handed Confederate attackers a bloody loss. Lieb commented that “the question, ‘Will the Negro Fight?’ was then and there settled for good.” The immigrants who chose the U.S. because of its ideology, helped save their adopted land from destruction. Under a nativist government, they would not have been welcomed to the uniformed ranks.

Strategic Strength

Perhaps no greater example of how diversity strengthens us exists than Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 struggle with what to do about emancipation. Enslaved people and some subordinate military commanders had made this the president’s problem. By flooding the lines, the runaways had forced local commanders to make a decision about what to do with them. Responses ranged from sending them back south to freeing and arming them. There needed to be a comprehensive federal response. By mid-1862, Lincoln had a solution, but would the country go along with it? Wisely, Lincoln pocketed his draft emancipation proclamation until victory at Antietam in the eastern theater of operations in September. From a position of strength, Lincoln then issued one of the most strategically devastating political actions of all time. On January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in territories of the rebelling states would be free.

In one single instance, Lincoln accomplished four strategic goals. First, he immediately undercut his adversaries’ greatest strength: a labor pool of about 4 million unpaid workers. Slavery propped up the Confederacy. Unpaid slaves worked jobs freeing White men to go to the front. Enslaved people accompanied Confederate armies as unpaid, ununiformed teamsters, laborers, cooks, saddlers, boatmen, launderers – in essence, logisticians. Only the mass of captive labor allowed the Confederates to field comparable forces to the U.S. and enabled their mobility. And Lincoln had told that base that if they got to U.S. lines, they would be free.

Secondly, in conjunction with the 1862 Militia Act and Confiscation Act, the Emancipation Proclamation took the adversaries’ greatest strength and used it to grow the U.S. Army. As states – and later the federal government – brought Black regiments to the field, the number of Black soldiers in the U.S. Army grew to 180,000.

Third, by making the destruction of slavery a war goal, Lincoln had entirely removed any chance of foreign intervention. England and France had abolished slavery in 1834 and 1848, respectively. Their public would not stand their governments supporting a cause bent on upholding slavery. Foreign intervention was perhaps the Confederacy’s best hope for independence. After 1862, its probability declined just as fast as the value of Confederate currency.

The first three strategic victories are all practical, and would be enough for any Bismarkian realpolitik-ist. But the fourth victory is more intangible. It cannot be measured on graphs or charts. It is measured in the conscience of a nation (if a pollster can figure out how to read that, American politics will experience a revolution). In applying a moral quality to the conflict beyond that of preserving the Union, Lincoln transformed the war into a cause linked to the opening of the Declaration of Independence, moving the needle on the “all men” section. The Proclamation gave the chance for “a new birth of freedom,” as its author would say a year later, and brought the war into line with American ideals. To be sure, many Americans opposed it, but enough supported it – especially in the Army – to bring Lincoln reelection in 1864, ensuring that the war would be prosecuted to the end.

One would think that this type of action would be a no-brainer, but political ideology can put a real damper on military common sense. For example, as British forces threatened Charleston, South Carolina in 1779-1780, and Patriot forces needed manpower, John Laurens brought up the option of arming enslaved men with the promise of purchasing their freedom after the war. So great was South Carolina’s fear of those they enslaved, they determined to fall to the British rather than arm Black men.6 And so, in 1780, they were besieged and forced to surrender, in the worst American defeat until Harper’s Ferry in 1862. Incidentally, the Confederacy, too, decided it would rather cease to exist than arm their enslaved men – in fairness, doing so would erase their entire reason for existence, so you can see where the cognitive dissonance might have broken their already-enfeebled brains. Like their forebears in 1780, Charlestonians of 1865 waved the white flag rather than overcome their prejudices.

Another classic case of prejudice and hatred erasing strategic gains is the example of Nazi Germany in eastern Europe during the Second World War. Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union in 1941, to destroy – as he called it – the “Jewish Bolshevist” regime of Josef Stalin.7 Having ensured he would not have to fight a two-front war (he thought), Hitler could now focus on his main objective of the war: conquering Russia, enslaving the less-than-human Slavic peoples, and making it land for all those perfect blonde-haired, blue-eyed Germans to inhabit.8 Hitler and the Nazi regime’s belief that Slavic peoples were inferior and only useful as slaves eliminated his greatest chance for success in Barbarossa.9

As much as Hitler hated Stalin and the Soviet Union, the peoples of eastern Europe hated the Soviet Union just as much – or more. Loss of autonomy, brutal governance, and mass poverty under the Soviet regime was the cause of this animosity. Had the Nazis capitalized on this, millions of willing and eager soldiers would have flocked to the cause. Instead, as Nazis entered eastern European towns, they treated the Slavs as their ideology had taught them. Civilians were robbed, beaten, raped, shot for sport, and rounded up into labor camps. Even still, hatred for the Russians and the desire for self-preservation, brought nearly a million eastern Europeans into the Wehrmacht – although the Nazis viewed them as auxiliary troops and placed little faith in them. The slave labor of millions of ethnic Slavs kept Hitler’s war machine fueled, but at the cost of an ever-increasing and effective guerilla war that kept his supply lines in the east tenuous, at best.10 Combined with an annoying tendency of the Soviet government to not surrender their country, Slavic resistance helped undermine Hitler’s goal of creating lebensraum to the east. Nazi ideology thus doomed Barbarossa from the start.11

Of course, this is not to say that the U.S. didn’t have our own missteps during World War II. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt assured Black community leaders that they would have a proportional representation in the draft, and the Selective Service and Training Act called for no discrimination, the Army remained segregated. This meant that Black and White inductees could not be housed or trained together. The Army had to build segregated training camps and induction facilities as well as create more separate units in the Army force structure. With White facilities and units as the priority, these could not be constructed and developed fast enough, so that by early 1943, 300,000 African-Americans had been selected but not yet inducted. Draft selection caused many Black Americans to lose their jobs which left them in limbo for an undetermined period of time while also depriving the Army of manpower it desperately needed to fight a two-front war. Segregation in the Army also caused local draft boards to have to determine the race of the registrant, which caused immense problems in the South, in Puerto Rico, and in the Southwest. When draft boards asked the War Department what to do about this, the War Department declined to issue directives on how to identify races – possibly because that might be too much like their adversaries. In short, racist policies hampered the ability of the War and Navy Departments to adequately man, train, and equip its fighting forces in the crucial years of 1943-1944.12

Racism isn’t just an awful moral stance, it also turns out to be inefficient and degrades your combat power.

One of the greatest strengths of the U.S. military has been its perceived ability to truly be a place where anyone, no matter their background, can rise to the level of their own merit. While this is not historically true given the exclusion of racial minorities, women, and gay, lesbian, and trans Americans across our history, in this case it is the public perception that is important. Because in a sense, it gives the American people a national embodiment of the opening lines of the Declaration – that all are created equal. And if all are equal, the military is then a diverse institution, able to gain talent from all across the nation and not restricted by prejudice. This makes us not just more efficient and deadly, but also an aspirational organization aligned with our aspirational Constitution, which each member is pledged to protect and defend. “To form a more perfect union…” could well be translated into, “To form a more perfect military.” In one sense, the U.S. military is an avenue for the so-called, “American Dream.” Or, more simply, where the individual can become one of many and yet remain themselves, and find a sense of belonging in something larger than themselves, and be seen for their merits rather than anything else.

Which is an idea more powerful than anything Boeing, Lockheed, General Dynamics, BAE, or Northrop Grumman can ever manufacture.

The opinions represented here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

- Charles Wadsworth Camp and World War I: War’s Dark Frame and A History of the 305th Field Artillery, 276. ↩︎

- Camp, History of the 305th Field Artillery, 226. ↩︎

- John Rees, “They Were Good Soldiers:” African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783 (Helion and Company, 2019), 173. ↩︎

- Rees, “They Were Good Soldiers,” 30. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Cobbs, The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers (Harvard University Press, 2017), 2-8. ↩︎

- Noel B. Poirer, “A Legacy of Integration: The African-American Citizen-Soldier and the Continental Army,” Army History, Fall 2002, 22-23. ↩︎

- https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/operation-barbarossa-and-germanys-failure-in-the-soviet-union ↩︎

- Paul Fleming, Jr., Operation Barbarossa: The Failure of Nazi Ideology at the Eastern Front http://cas.loyno.edu/sites/chn.loyno.edu/files/Operation%20Barbarossa_The%20Failure%20of%20Nazi%20Ideology%20at%20the%20Eastern%20Front.pdf ↩︎

- Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Ideology: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/victims-of-the-nazi-era-nazi-racial-ideology ↩︎

- https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/nazi-forced-labor-policy-eastern-europe ↩︎

- Fleming, Operation Barbarossa: The Failure of Nazi Ideology at the Eastern Front http://cas.loyno.edu/sites/chn.loyno.edu/files/Operation%20Barbarossa_The%20Failure%20of%20Nazi%20Ideology%20at%20the%20Eastern%20Front.pdf ↩︎

- James Huston, “Selective Service in World War II,” Current History, Vol. 54, No. 322 (June, 1986), pp. 345-350. George Flynn, “Selective Service and American Blacks During World War II,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 69 No. 1 (Winter, 1984), pp 14-25. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.